Innovation Ecosystems: Is there a Cost to Collaboration?

More and more companies are using innovation ecosystems to bring better products to market. But Ron Adner, Associate Professor of Business Administration, says all of this collaboration comes at a cost.

More and more companies are using innovation ecosystems to bring better products to market. But Ron Adner, Associate Professor of Business Administration, says all this collaboration comes at a cost.

For many companies, however, such attempts at innovation result in costly failures characterized by broken promises and missed expectations. This is because, along with new opportunities, innovating in ecosystems presents new sets of challenges. What we call “seamless collaboration” in cases of success, we relabel “fragile interdependence” when the outcome disappoints.

Across the spectrum of economic and social activity, we are witnessing a crescendo of collaborative aspiration. In industry after industry—the automotive sector’s recent foray into electric vehicles, the security sector’s visions of comprehensive threat assessment, the health care industry’s move to electronic medical records, the list goes on—firms are signing on to increasingly exciting value propositions. Delivering on these promises, however, ties firms to greater complexity: longer chains of intermediaries who all must agree to adopt the innovative vision, and larger sets of so-called complementors who must overcome their own innovation challenges for the focal firm’s efforts to matter.

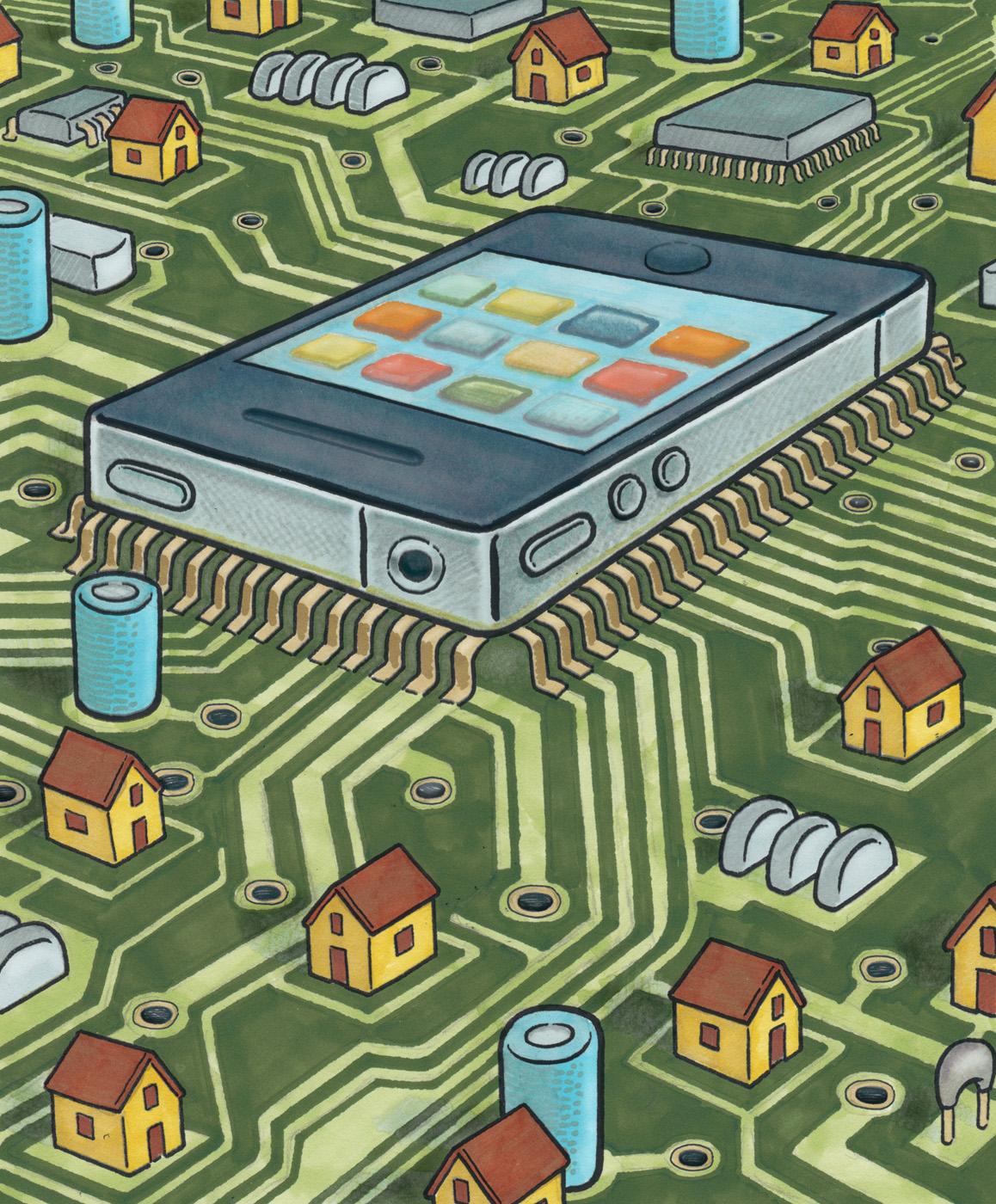

In this way, innovation ecosystems present a new set of strategy and management challenges. To see the contrast, look no further than the examples set by Nokia and Apple. Through the first half of the last decade, Finnish telecommunications giant Nokia held sway in a market defined by product-based competition. Moreover, it knew it wanted to pursue an ecosystem approach when it created the Symbian operating system in 1998 and attempted to entice developers to create applications for the platform. It had long been Nokia’s vision that having software on phones would greatly enhance its core offerings.

But Nokia didn’t fully understand what needed to change for this to work. For example, an important element of Nokia’s competitive advantage rested in its unmatched ability to customize a wide variety of phones for operators. This enabled Nokia to offer an array of choices to operators and, through them, to consumers. There was, however, an unintended, and unmitigated, consequence in pursuing this strategy: the high customization costs and indirect path to market that participating in the Symbian platform imposed on software developers. This limited the attractiveness of the offer from the developers’ perspective, which, in turn, handicapped the entire vision. In this way, Nokia’s product strategy undermined its ecosystem strategy.

In contrast, Apple’s iPhone offered developers a uniform development environment and a direct path to market. Apple also had a sufficiently large base of iPhone users to motivate developers’ efforts when it launched its App Store in 2008. Nokia’s smart phone vision preceded Apple’s by a decade. But because the company built its strategy around its product business, with complementors in the periphery, its attempt at ecosystem innovation floundered. While Apple’s laserlike focus never wavers from its own bottom line, the company prioritized its complementor strategy once it decided to pursue an ecosystem approach (as witnessed, for example, by developers’ prominence at Apple product launches and in its advertising.)

Nokia still makes great phones, but in the mobile phone market hardware is no longer enough. Their phones remain remarkable as products, but they are impoverished as solutions. As the competition shifted from products to ecosystems, the very essence of the game changed under Nokia’s feet. Its recent tie-up with Microsoft is an attempt to reposition itself in a world of joint value creation. While the wisdom of this specific choice has yet to be revealed (I have my doubts), the need to make a new choice was long overdue.

Success in an innovation ecosystem is rooted in the same principles of competitive advantage and value creation that have always been at the heart of strategy. But the way in which these principles are applied has changed. When we depend on others for our success, the ways in which we prioritize opportunities and threats, how we think about market timing and positioning, indeed the very ways in which we measure and reward success all need to change to explicitly account for this dependence.

The message is clear: The collaborative advantage at the heart of ecosystem-based strategies comes with added peril and promise. Leaders and organizations that go down this path must do so with eyes wide open, not only to the potential benefits of a well-executed ecosystem strategy but also to the risks involved. For the next wave of industry leaders, confronting the new paradigms brought about by innovation ecosystems will not be an option. It will be mandatory.

March 2011