Panelists Discuss Big Data and the Future of Political Campaigns

The event, part of the Britt Technology Impact Series, focused on technological advances that are allowing campaigns to target voters and motivate them to cast their ballot on Election Day.

A week before the November 6 presidential elections, it’s already clear who one big winner of the 2012 campaign season will be: purveyors of billions of bytes of data on tens of millions of American voters.

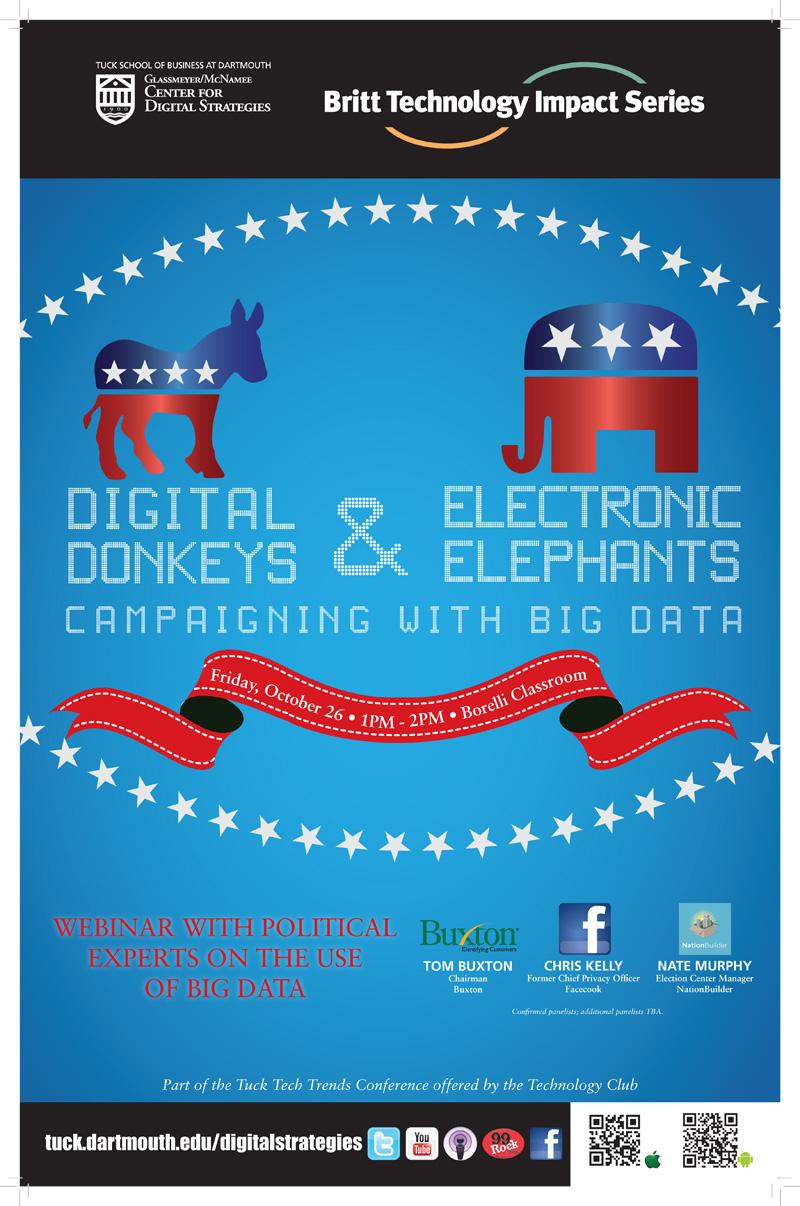

That was the message from three panelists who spoke via video-link on October 26 to a group of Tuck students and moderator Joseph Bafumi, an associate professor of government at Dartmouth College. The event, part of the Britt Technology Impact Series organized by Tuck's Glassmeyer/McNamee Center for Digital Strategies, was titled “Digital Donkeys & Electronic Elephants: Campaigning With Big Data,” and focused on technological advances that are allowing campaigns to target voters and motivate them to cast their ballot on Election Day. At play are data mining practices that have been pioneered by big companies such as Amazon and Wal-Mart in consumer marketing.

It's a lot like looking at customers for a company, Tom Buxton, chairman of consumer analytics firm Buxton, told students. “In the political world, you can say who is the voter and what do you look like? The look-alike concept applies to the voter, the donor, or the consumer of any product.”

President Obama’s campaign has mined data to find that its supporters are more likely to listen to smooth jazz, eat at Red Lobster, and shop at Burlington Coat Factory, while Romney backers have a taste for Sam Adams beer, dine at Olive Garden, and watch college football, according to a recent New York Times report.

Having that sort of information alone isn’t enough, said Chris Kelly, Facebook’s chief privacy officer until 2010, when he left to run for California attorney general. Campaigns also have to design useful models and strategies to translate the information into efficient campaign messages—whether it’s direct mail, television advertising or sending volunteers to knock on doors.

“Computing allows campaigns to operationalize on big data,” said Kelly, who now works for a company that makes data-mining applications for mobile devices. “You have to figure out how to take all this information and do something that’s useful.”

During Kelly’s electoral bid, his campaign ran a successful pilot program utilizing voter files to find infrequent voters and ask their Facebook friends to contact them to encourage voter outreach. Kelly lost his campaign, but said that the effort helped him and his staff glean insight into big data strategies.

Mining big data is no longer solely the province of the Romney and Obama campaigns, both of which have raised about $1 billion. “Obama has essentially set up a tech company startup both times that he’s run, but most campaigns don’t have those kind of resources,” said Nate Murphy, election center manager for NationBuilder, a nationwide voter database. “This has been the first time you’ve seen people running for state legislature using big data.”

The panelists acknowledged that the growing use of data-mining raises privacy concerns—and that voters can be turned off by the “creep factor” of having campaigns know detailed information about their shopping preferences or web-surfing history. “If you target the right message to the right person, they’re happy to see the message,” said Buxton. “If you send the wrong message they’re upset and think you have too much information. There’s no value in using that information incorrectly.”

The use of micro-targeted messaging also raises broader questions for the functioning of democracy, the panelists said. Democracy is not like selling a consumer shoes or breakfast cereal—where guiding a specifically tailored marketing approach yields a sale. Competing ideas are necessary to the functioning of a healthy public sphere, and the splintering of conservative and liberal media on the Internet and cable television already allows citizens to live in a loop of self-reinforcing political messages.

“We may need to try to create spaces where people who are tracked in their receipt of information mix it up a little bit,” said Kelly. “People are self-selecting in media already…but there is a risk where people end up in this echo chamber. We’ve got to find a way to keep talking to each other.”

Ensuring that there is greater transparency in how personal data is collected is in the interest of both the public and purveyors of data-mining. It’s also vital that big data not be the sole province of the two major political parties, said Murphy, whose company is marketing its data-mining tools to grassroots campaigns from school boards to city councils. “The issue moving forward is do we allow the two parties to control big data?” he said. “Do you have to ask permission to use that big data? Or do you get to rely on your own abilities?”