When Does Waiting in Line Seem Unfair?

Tuck professor Laurens Debo examines a new method for dealing with product waitlists.

In a new working paper, Tuck professor Laurens Debo and Chicago Booth’s Luyi Yang examine “referral priority” programs—where firms allow customers on a waitlist to move up in line if they refer a friend to the firm—and find that they can sometimes work well. However, they also can be too successful, clogging the system with too many customers and increasing wait times.

In 2014, Stanford graduates Vlad Tenev and Baiju Bhatt created a mobile app with instantaneous appeal. Robinhood, as the app is named, is a commission-free stock trading tool targeted at millennials who are turned off by the cost and inconvenience of traditional trading services like E-Trade and Scottrade. Word-of-mouth about Robinhood spread quickly, after the invite-only beta version was released, and before long 700,000 people had joined the waitlist for the official product launch. As Robinhood built up the capacity of its servers and processors, it would take customers off the waitlist and give them access to the app.

The beta version received positive reviews, but the wildfire-like growth of the waitlist was also due to a decision Tenev and Bhatt made about promoting the service: they allowed wait-list customers to move up in line if they referred a friend to the app.

Customer-reward programs aren’t new, but Robinhood’s method was a bit unconventional. Most reward programs give customers a discount for referring friends. Robinhood was, in effect, rewarding customers by shortening their time on the waitlist. This approach has gained popularity in recent years—it’s been used by LBRY and x.ai, for example—and, on the face of it, the method is a win-win. Companies get more customers, and customers get faster access to a limited product. But as Tuck associate professor Laurens Debo shows in a new working paper, co-written with Luyi Yang of Chicago Booth, the “referral priority” program has the potential to do more harm than good.

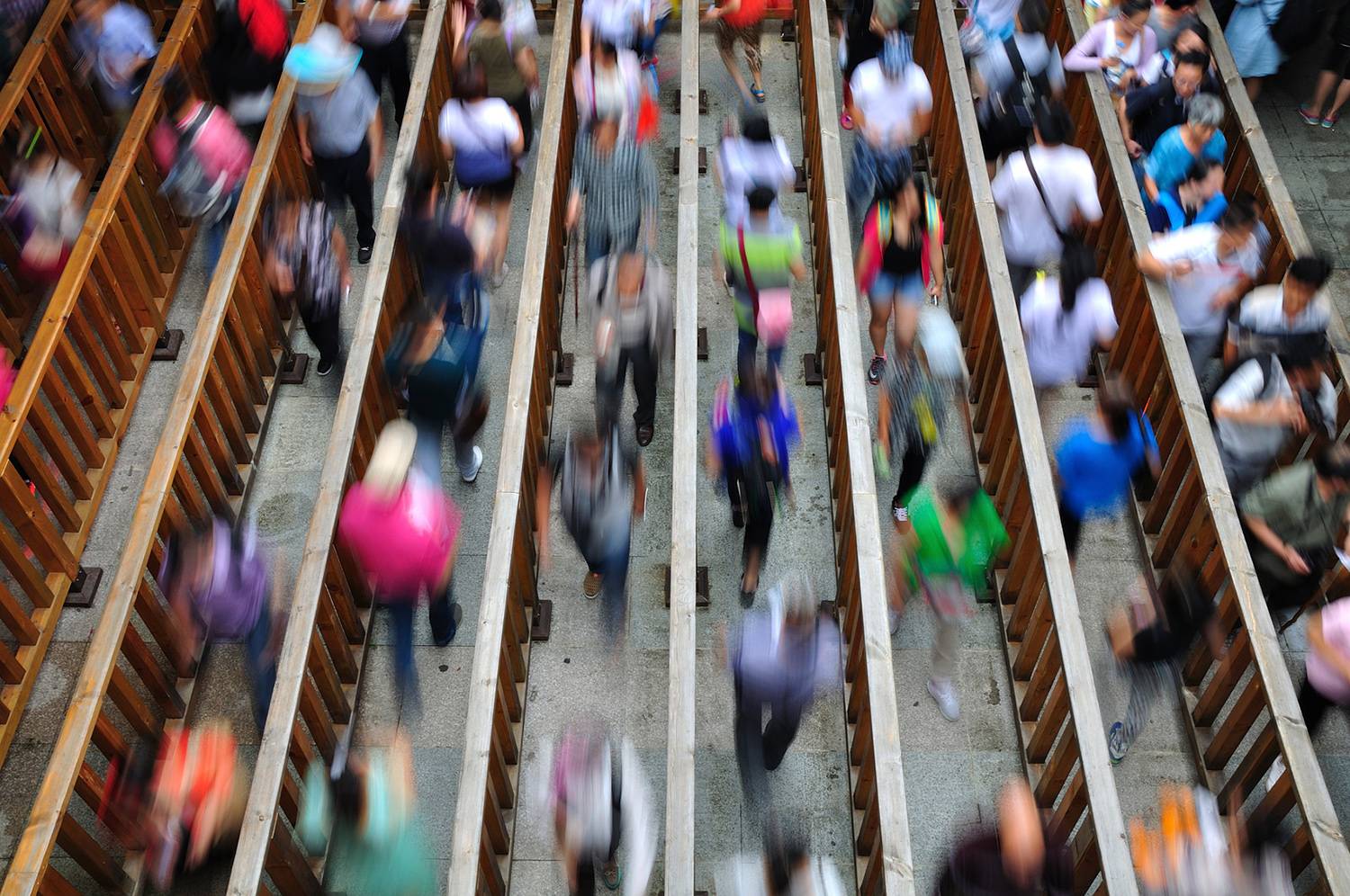

Debo and Yang are operations experts who specialize in queuing theory, the study of how companies balance customer demand with their own limited abilities to serve that demand. If you’ve ever waited in line for a bagel, or been put on hold during a call to the cable company, you already have a sense of queuing theory’s importance to a business’s success. Make customers wait too long and you will lose their business. But if you spend too much on labor to serve customers, you might go out of business. In their paper, “Invite A Friend And You’ll Move Up In Line: Leveraging Social Ties Via Operational Incentives,” the authors combine queuing theory with game theory—the study of how human decision making impacts other human behavior—to learn more about the nature of referral priority programs. Game theory comes into play in this context because referral priority programs allow some customers to cut the line, and that can make other customers upset and possibly spur them to leave the system altogether.

“Our main motivation is to investigate how technology is going to change the way people queue,” Debo says. “With mobile apps and websites, customers have more choice, so how does that impact their decision to join a queue, gain priority in a queue, or go to a different service provider?”

In order to study referral priority programs, and understand more about when they can be beneficial, Debo and Yang created a mathematical model of customers’ rational decision making in a queuing context. They found that referral priority programs, while sometimes effective, have a kind of hidden self-destruct button. If the referral program is too successful, it will make the system more congested, leading to longer wait times. At a certain point, prospective customers will think the wait time is just too long, and they won’t even get in line. Alternatively, the referral system could make a waiting customer’s wait even longer, because other customers are jumping ahead of them by referring friends. And breaking the long-standing custom of first-come, first-served can seem unfair.

“Firms really have to exercise their discretion when they’re faced with new technologically enabled mechanisms,” Yang says. “At first blush, these mechanisms may seem to be very appealing, but you have to decide if it’s a good fit for your company and your market conditions.”

As for Robinhood? It’s an example of what can happen when a referral priority program goes well. Today it’s one of the fastest-growing brokerages, with almost one million users and more than $3 billion in trading volume.