What If Foreign Imports Create U.S. Jobs?

As a populist backlash against globalism fuels cries for protectionism, our research suggests that foreign inputs benefit domestic firms, making them more competitive in the global economy.

Tuck professor Teresa Fort’s research offers a counterpoint to the “prevailing anti-globalization rhetoric.”

Globalization is under attack. The backlash was manifested most dramatically in the choice of British voters to leave the European Union last June and the election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency in November.

Two days after Trump’s victory, Edward Alden wrote in Fortune magazine that “Wisconsin has not voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1984. Pennsylvania and Michigan have not done so since 1988. Yet on Tuesday, all three voted for Donald Trump, blowing through the electoral ‘firewall’ that Hillary Clinton had thought would carry her to the White House.”

Alden notes that voters in those states, and others that have endured prolonged declines in manufacturing, see themselves as losers in a global competition. Their disaffection is deeply felt and crosses party lines. Though Trump and Bernie Sanders occupy opposite ends of the political spectrum, opposition to NAFTA and the TPP was a reliable applause line for both men during the 2016 campaign.

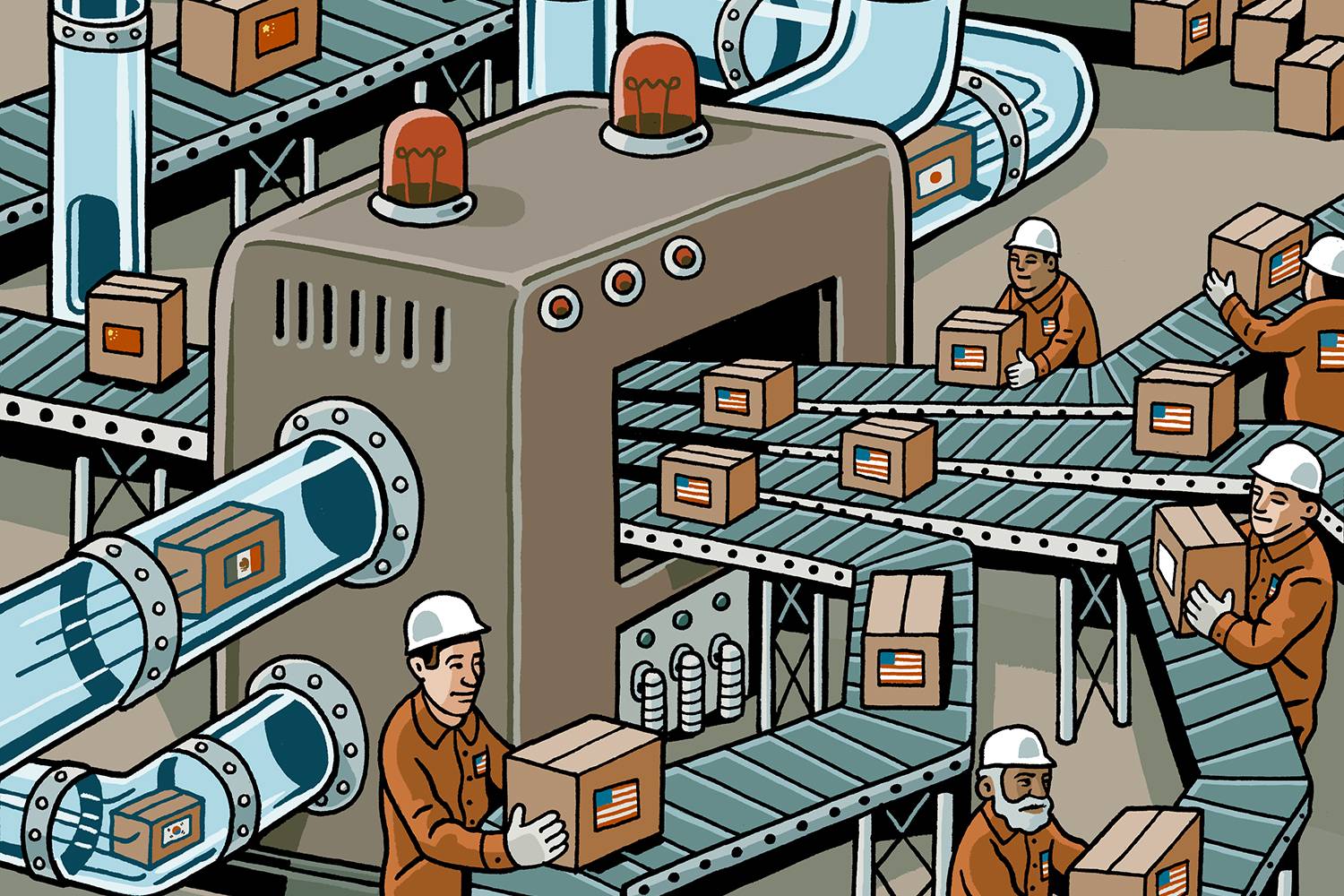

There’s no question that global trade has hurt some, even as it has benefited others. But that assessment paints an incomplete picture. My research with colleagues Pol Antràs of Harvard University and Felix Tintelnot of the University of Chicago focuses on a potentially positive effect of trade, namely the opportunity for firms to access cheaper inputs from foreign suppliers. Inputs are materials or components used to manufacture finished goods, such as sheet steel or windshield wiper blades in the automobile business. We found that when companies reduced costs by sourcing inputs from China, they were able to use those savings to buy more components from other suppliers, not only in China and other countries, but also in the United States.

Our research offers a counterpoint to the prevailing anti-globalization rhetoric, which is based on the false supposition that trade is a zero-sum game and that winners and losers are divided by nationality. Our data support a different viewpoint, in which trade typically benefits those who engage in it. The winners and losers in the global marketplace are determined less by the countries in which they are based than by their ability—or inability—to get the most value from an increasingly international supply chain.

Larger firms are typically better able than smaller ones to take advantage of global sourcing because they can more easily cover the costs of opening new supply channels. The advantages from these new channels are significant. We calculate that an average U.S. firm sourcing from all 66 foreign countries in our sample faces around 9 percent lower input costs than a purely domestic firm, and consequently has sales that are approximately 32 percent larger. A firm in the 90th percentile of foreign sourcing in our data imports 47 percent of its inputs, implying a 30 percent cost savings and a 176 percent increase in its sales.

So for companies with sufficient scale, international trade can be very good business indeed. But how does that affect American workers?

So for companies with sufficient scale, international trade can be very good business indeed. But how does that affect American workers? Our research suggests it benefits those who work for firms able to take advantage of global supply chains, or companies who supply those firms. To use our automobile analogy, a company that supplies its Michigan assembly plant with lower-cost headlights from China can use those savings to source more engine mounts from Ohio. While that benefits workers in China, it’s also good for folks in Michigan and Ohio.

That brings us to the policy question. President Trump rode to the White House on a wave of populist anger stoked, among other things, by his promises to repeal NAFTA, scrap the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and force China to deal with the United States on his terms. During the campaign, he invoked the possibility of a 45 percent tariff on Chinese imports, and he continues to suggest that protectionist policies will level the playing field. In contrast, our work shows that shutting off foreign inputs for U.S. firms will reduce their competitiveness in the global marketplace, and will lead to higher prices for U.S. consumers.

Our research points out a big potential cost of limiting international trade—the collateral damage it could inflict on U.S. firms, including not only those that benefit from low-cost foreign inputs, but also their domestic suppliers. Even if trade partners did not retaliate against U.S. protectionism with trade barriers of their own, higher domestic tariffs would decrease the competitiveness of U.S. firms, both at home and abroad and lead to higher prices for consumers.

This article originally appeared in print in the summer 2017 issue of Tuck Today magazine.