The Human Element

Forget technology. It's people that are keeping information security professionals up at night, says professor Eric Johnson.

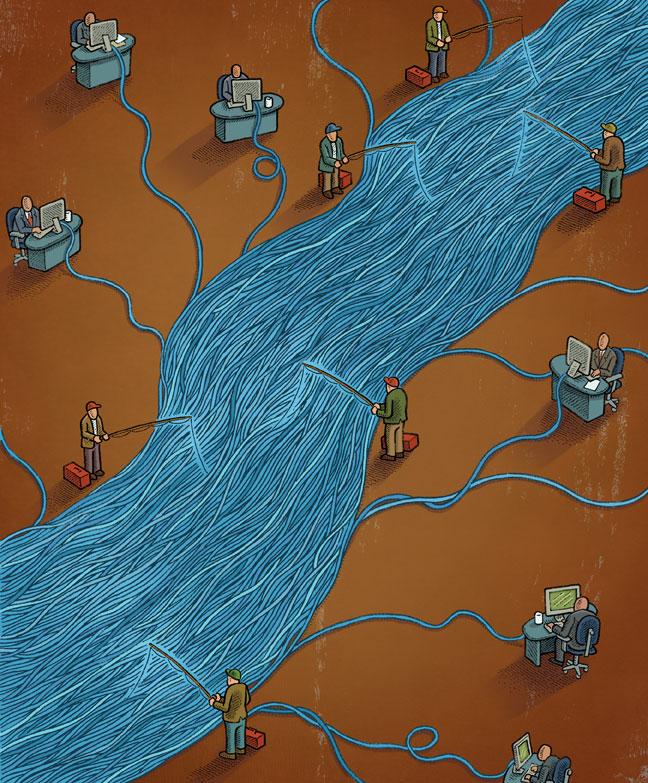

We are connected. The number of devices accessing the Internet today easily exceeds the world's population and will likely reach 50 billion by the end of the decade. This connectivity has transformed how we do business and the way we live, but it also has a dark side. With trillions of emails, instant messages, and social media posts floating around in cyberspace, information is now harder than ever to protect.

Just ask the hundreds of millions of consumers who had their personal data compromised this year, or the tens of millions who fell victim to identity theft. From the shuttered Panda House restaurant in Hanover, N.H., to Japan's Sony Corporation, managers are left struggling to explain security breaches to angry customers. In some instances, the breaches are the work of sophisticated criminals who hack their way into well-protected networks. But, as is often the case, many failures defy explanation. Earlier this fall, administrators at Stanford Hospital were at a loss to explain how a spreadsheet containing the names of 20,000 emergency room patients ended up on a public website. They are not alone. Indeed, few leaders in business or government these days rest easy knowing their secrets are safe and secure.

For many organizations the most challenging information security frontier is people."

Although much has been done to improve the technological side of connectivity, for many organizations the most challenging information security frontier is people. Corporations and governments alike face staggering risks from members of their own organizations. Whether willful or inadvertent, human-induced leaks fueled by mass distribution on sites like WikiLeaks can create breathtaking exposure. Few, for example, could have imagined the reputational damage that one disgruntled U.S. Army private could cause. With the click of a mouse, Private Bradley Manning exposed vast diplomatic secrets to a curious world and forever changed the way we perceive state privacy.

Just as damaging are simple mistakes, which can lead to large-scale losses of corporate intellectual property. An errant entry on an email recipient list by an employee in Chevron's risk group, for instance, led to the accidental distribution of spreadsheets detailing the firm's petroleum-trading strategy to several media organizations. Of course those bent on stealing intellectual property can now slip vast numbers of secrets into their pockets on a flash drive or smartphone. From investment banks to defense contractors, insiders have walked away with everything from valuable trading algorithms to product plans.

Insider theft and disclosure blunders are not new. But the potential magnitude of the losses they incur is growing. Meanwhile, targeted threats toward individuals are increasing, with ever-more sophisticated deceptions. The consumerization of technology has simply added to the human challenge. Smartphones and tablets beautifully integrate connectivity into every aspect of our lives, blending the personal and professional so seamlessly that we can now perform work-related duties on the soccer field sideline and home-related tasks from the boardroom. New so-called “spear-phishing” tactics are taking advantage of this blurred life, deceiving executives through carefully crafted emails appearing to come from spouses, children, or friends. Simply clicking on what seems like an attached photo or embedded link can open digital doors, welcoming intruders into the corporate network.

At a pair of workshops recently hosted by Tuck's Center for Digital Strategies in Zurich and Hanover, information security chiefs from 40 of world's largest companies made it very clear just how nervous they were. Nearly 90 percent of participants said that information risks have significantly or modestly increased in the past 12 months; 70 percent felt that it is at least somewhat likely that their firm will experience a significant disruption or breach in the next year; and more than 80 percent argued that the human-related risks were more troublesome than the technical challenges facing their organizations.

In many ways, learning to manage these threats parallels the quality revolution of the 1980s, when manufacturers the world over adopted methods like total quality management, lean production, and six sigma and triggered a fundamental change in the philosophy of quality improvement. From the shop floor to the boardroom, quality became a universal focus. Similarly, the scope of the information security challenge today is simply too great for one department to handle alone. It is everyone's concern and must be incorporated into every level of the organization.

This starts with education. Traditional security education, which includes messages designed to improve user hygiene with passwords or Web surfing, has limited impact. Instead education needs to be integrated directly into the employee workflow, embedding information risk considerations into business decisions. Following the lessons from quality improvement, companies must also empower employees with user-friendly security tools, while employees themselves need to understand the nature of the threats in order to make appropriate risk decisions. Simply telling the security department to protect everyone leads to overly restrictive controls that slow business and encourage people to look for workarounds. The workarounds themselves—such as emailing a spreadsheet to a Gmail account because the corporate network cannot be accessed from home—only create larger risks. Taking a lesson from six sigma, security specialists need to involve stakeholders and the entire user community in developing effective controls.

The challenges are great, and everyone must be part of the solution. If information security were merely a matter of building better systems, we would have done so already. Instead, we are dealing with the most powerful and unpredictable computer of them all—the human mind.