The Earth Keeper

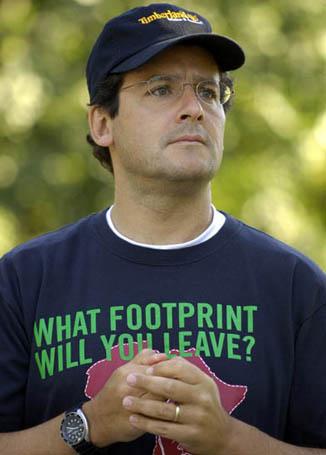

Timberland CEO Jeff Swartz T’84 is winning people over—one eco-friendly piece of gear at a time—with a deeply held belief that doing good in the world is also good for the bottom line. Will competitors follow suit?

Jeff Swartz T'84 padded downstairs to his home gym in the dark predawn of a New England winter morning, put on his headphones, and climbed onto his rowing machine. He rowed for nearly an hour, legs burning and sweat dripping onto the carpet. After he was through, he removed his headphones, slid off the machine's hard plastic seat, and sat on the floor.

It was a rare moment of stillness in a nonstop life, but Swartz's mind, as usual, buzzed. He reflected on a recent trip he took to Egypt with his wife and three sons, where they saw the Nile, the pyramids, and the temples at Karnak, just before the protests that sparked a revolution. His son told him that the Great Pyramid of Giza was the tallest man-made structure on Earth until the 1840s, and it occurred to him that it stood as an amalgam of so many things—hopes and aspirations, despotism and creativity—and yet its enduring grandeur stood in such contrast to the mess of modern Egypt.

His thoughts drifted to the canyons of buildings in New York City, where he had visited the previous week, and how they seemed, in a way, like pyramids—monuments to a misguided notion of progress. At that moment, it occurred to him that he had just rowed 10,000 meters, according to the readout on the electronic monitor. And yet, in reality, he had gone nowhere. That, he realized, was the perfect metaphor for trying to effect social change.

The truth is that, as CEO of Timberland, the New Hampshire-based global manufacturer of footwear, clothing, and accessories, Jeff Swartz has traveled much farther than 10,000 meters in the effort to effect social and environmental change. But he has the type of vision that is never satisfied, which is why it's not unusual for him to wake at obscene hours of the morning with a mind that never rests.

Under Swartz's watch, from 1989 to 2010, Timberland's revenues grew from $156 million to $1.4 billion. Its products now span the outdoor, urban, and fashion worlds and are booming in new markets like Asia, which has 71 Timberland specialty retail stores and 19 factory outlets.

At the same time, along with a small vanguard of other forward-thinking companies, Timberland has evolved into a kind of corporate explorer, navigating uncharted territory at the intersection of business and corporate social responsibility. This is, in large part, thanks to Swartz, whose business philosophy is rooted in the belief that it's not about what you do but who you are—and that businesses not only have an opportunity but a responsibility to do good for the world by using the power of the market.

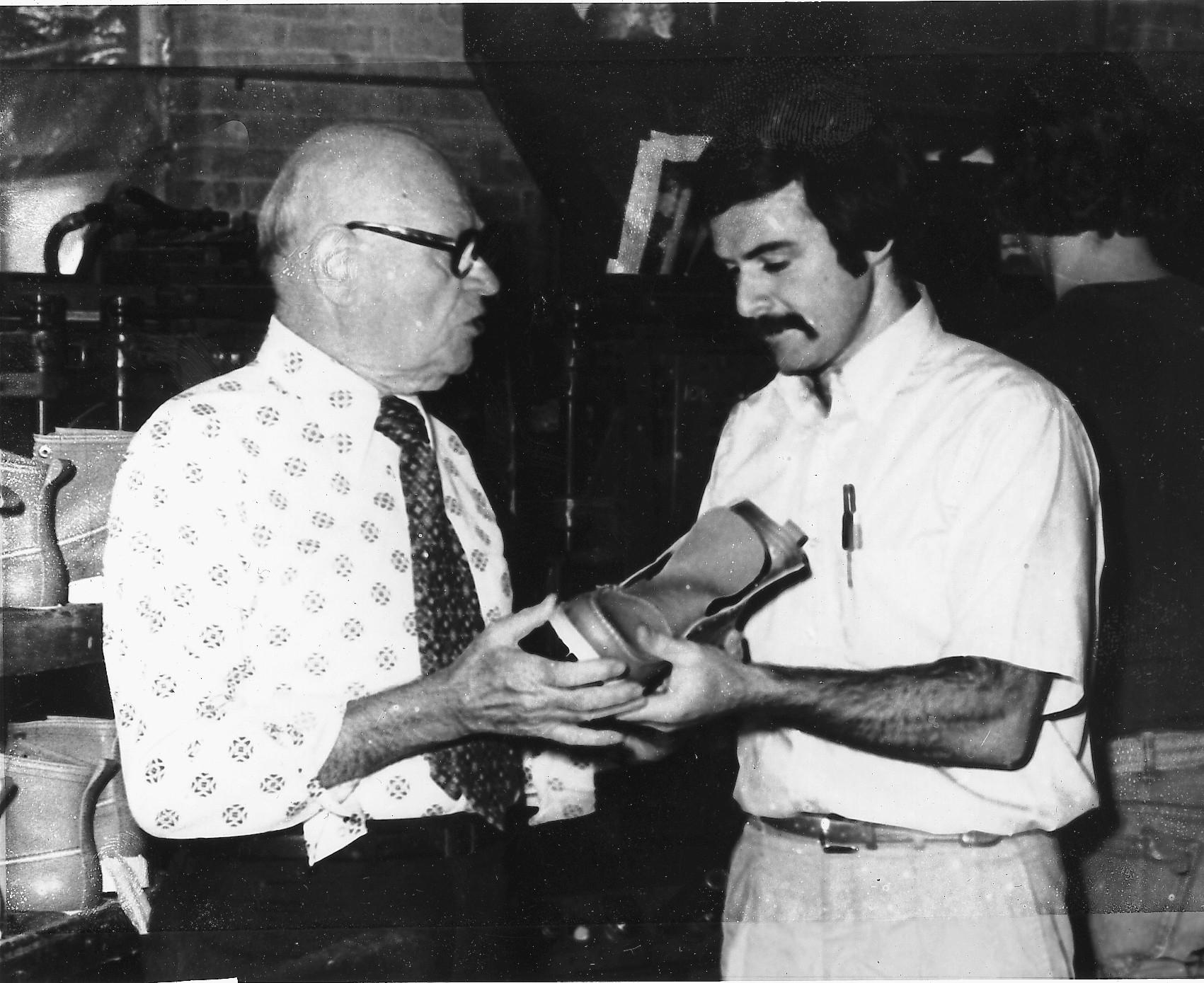

Jeff Swartz is fond of describing Timberland's 59-year evolution in three parts: boots, brand, and belief. Nathan Swartz, Jeff's grandfather and an immigrant cobbler, first bought a half interest in the Abington Shoe Company in Abington, Mass., just south of Boston, in 1952. With the stitching skills of a master craftsman, Nathan grew the company on the quality and durability of its innovative waterproof boots and then retired in 1968, leaving the company to the next Swartz generation. The company moved to New Hampshire a few years later and developed its guaranteed-waterproof work boots, producing them under the Timberland name starting in 1973. Sidney Swartz, Jeff's father and, like Nathan, another commanding man of few words, helped introduce the company's first ad campaign in 1976, roll out its first casual shoe model in 1978, and expand internationally in 1980, first to Italy. He also helped take Timberland from strong New England boot maker to purveyor of an aesthetic and a lifestyle.

Then it was the third generation's turn. While Jeff broadened the company's reach, he also started seamlessly integrating the beliefs behind the brand with the company's products and activism. In 1988, Timberland established a partnership with City Year, a nonprofit youth service, by outfitting the corps in boots and apparel. The relationship helped set an example for how companies and nonprofits could work together to further their missions.

In 1992, he also launched the company's Path of Service program, which offers all Timberland employees 40 hours of annual paid time off for community-service projects and up to six months for paid service sabbaticals. "We found a tremendous kindred spirit [in Jeff], who was seeking to do in the private sector the same kinds of things we were seeking to do in the nonprofit world," says Michael Brown, co-founder and CEO of City Year. "And we realized that those lines were rapidly blurring. As Swartz is fond of saying, customers don't check their beliefs at the door when they enter a store."

Nathan and Sydney Swartz.

Arguably, Swartz's childhood spent in a factory run by a practical, hard-working family played a role in the development of his brand of CEO—one more inclined to baseball caps than suits. Though Swartz jokes that growing up sweeping floors in the New England factory is why he prohibits child labor in his own factories, he sees the experience as a gift. He insists that he inherited his deep-seated beliefs in sustainability and community service from his father and grandfather. His own gift is the power of storytelling to help other people believe in those values too.

Like the story about walking through the stitching room as a kid and watching his grandfather, Nathan, bend down to pick up one-pin bobbins that had fallen on the floor. Swartz contends it was the practice of an age-old conservationist philosophy: reduce, reuse, recycle. His father, Sidney, didn't see it the same way. "He said that was just about the fact that we had no money, and if we weren't careful about resources we'd have gone out of business,'" says Swartz. Later, at age 11, Swartz learned about the symbiotic relationship between a business and its community. "I'm standing upstairs, 11 years old, and I'm Sidney's son, so I'm not swaggering but I know who I am, right?" says Swartz. And then off go the horns of the municipal fire alarm in the tiny community of Newmarket, N.H. "The sound intrudes on the sonnet of the factory, and then the sonnet responds and machines stop working." The workers started walking out, and Swartz ran to find his father to ask what was happening.

"What do you mean, what's going on?" his dad said over the din. "There's a fire in town."

"No, no, I heard that. I mean, where are people going?" said Jeff. "To put out the fire, you genius." The boy looked at his father. "Look, this is Newmarket. It's not like Newton or Brookline. We don't have a fire department. We have a volunteer fire department, so it works like this: The fire gets started and someone sees it, the alarm goes off, people leave their machines, put out the fire, and we lose the production that they could have made when they were otherwise putting out the fire. But if they don't, our building burns down. If our building burns down, you don't go to college. Is that clear?" It was clear, and some 40 years later, Swartz told his father this story to illustrate a value Timberland has held since the beginning.

"So I told him the story, and he says, 'What's your point?'" says Swartz. "We can't exist as a for-profit business without an active interrelationship with the community that we live and work in." Now, of course, the community is a lot larger.

For me, Tuck was most attractive because it was a place I felt I could learn how to be an effective business leader without sacrificing my personal values.

Although Jeff Swartz's parents were strong believers in public education, they enrolled him in Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., because he was getting into trouble at home. He earned a degree in comparative literature at Brown University and immediately enrolled at Tuck, whose strong values appealed to Swartz.

"Tuck's values—integrity, excellence, community— were as familiar to me as my first-generation entrepreneur grandfather or my civic-activist mother," says Swartz. "Yes, it had a beautiful campus—still does—and yes, it had a well-earned reputation as being one of the best business schools in the county—still does—and that was all great. But for me, Tuck was most attractive because it was a place I felt I could learn how to be an effective business leader without sacrificing my personal values."

After Tuck, Swartz worked stints in operations at Alpha Industries, a tech manufacturer in Massachusetts, and at Lotus Development Corporation before returning to work for his father at Timberland in 1986. From sweeping floors up to serving as chief operations officer, Swartz worked in a variety of functional areas with the company.

As a result, Swartz not only deeply understands the inner gears of the business but also the people who run it. This may be part of the reason why Timberland is a uniquely people-friendly place to work, lauded by publications such as Fortune, Outside, and Working Mother as a top employer. At its Stratham, N.H., headquarters, there's an on-site day care center, a free fitness center, and snowshoes, kayaks, and canoes available to borrow. Staffers are offered flexible workweeks and take part in two global companywide service days.

"At Timberland, it's not only OK to bring your values with you to the workplace, it's expected," says Gordon Peterson T'84, vice president of change management, business transformation, who met Jeff Swartz and Jeff's future wife, Debbie, on their first day at Tuck. He says Swartz's belief that everyone has good inside of them and his ability to challenge employees to bring their skills and values to the company inspires them to rise to their best. The approach, he says, is uniquely energizing, and Swartz is a large part of the reason why Peterson has spent more than two decades at Timberland.

"We all feel pretty lucky to work here," says Betsy Blaisdell, Timberland's senior manager of environmental stewardship. "A huge chunk of that has to do with Jeff. He truly believes in the business model of commerce and justice, and he's effectively sold it. We believe in it, and we believe every other business should believe in it." Charged with Swartz's infectious enthusiasm and values, many employees have a surety of purpose but also a deep sense of inventiveness, which might explain why Timberland has come up with some unique ideas.

One was born in a Whole Foods Market in Massachusetts; this is another story Jeff Swartz likes to tell. One day, he came home from Whole Foods with regular old apples, and his wife, Debbie, sent him, slightly irritated, back to the store for organic apples. "So now I was forced to look at the point of sale because they couldn't just be apples, they had to be organic apples," says Swartz. "I'm looking at their handlettered signs in Whole Foods, and I admit it's kind of cool storytelling. I was reading about Granny Smith on her farm in Vermont and blah blah blah." As he looked more closely at the signs and the convincingly charming stories about farmers, his eye opened to what he calls storytelling at retail. He roamed about the store, looking at labels, and eventually returned to Debbie with the proper apples—and a brain full of ideas.

Swartz came into the office on Monday with a directive: put a nutrition-like label on Timberland's shoeboxes that would not only tell the appealing story of the Dominican artisan who hand sews the shoes but also why Timberland's leather is environmentally superior to other companies' and how their factories are more people friendly. His employees were a bit confused.

"They were saying, 'Are you out of your mind?'" says Swartz. One employee asked why a company would voluntarily disclose such information. But that was part of the point: Disclosing their own metrics would encourage both Timberland and its competitors to clean up their operations in an industry known for manufacturing processes that were not environmentally friendly. It would also offer consumers tools to make informed decisions about their purchases. Although the logistics seemed insurmountable to his employees, it was a rare moment when Swartz put his foot down.

In 2006, the label appeared on all Timberland shoeboxes, evolving into the company's current Green Index a year later. It looks much like a standard nutritional label you might find on the back of a cereal box. But rather than providing information on calories and grams of fat, the Green Index includes information on the chemicals, ecoconscious materials, and renewable energy used in the product's manufacturing process. From Swartz's perspective, the label is at once a great success and a great failure.

"Listen, we're a place where passion and principle have to get worked out, so the Green Index label is an example of something to be proud of and something to be incredibly frustrated with," says Swartz. The label has encouraged Timberland to keep reducing its emissions and improving the environmental health of their operations. Consumers have appreciated the label, and yet they have nothing to compare it to. Timberland has offered to give away the technology for free, yet no other brands have followed. The label did not spark a revolution, which was its purpose, but it did further the conversation. And this is perhaps Swartz's best asset: the ability to bend an ear.

As to be expected, Timberland has encountered countless other challenges in the company's search for a model of commerce that intertwines profitability and sustainability. In 2005, Timberland collaborated with the actor Don Cheadle to create a boot whose proceeds would go to Darfur aid. Timberland shipped 1,000 pairs to stores around the world. Cheadle was enthusiastic. Swartz was enthusiastic. And yet the shoes sat on shelves. One day, visiting a store in a mall in New York's Westchester County, Swartz decided to find out for himself why they weren't selling by asking a customer what she thought.

"I was chasing her around this store, stalking her in the nicest possible way," says Swartz. "And so I help her get what she needs for her husband or whatever it is and then I drag her over, you know, existentially, to the Darfur thing and she's like, "No." I said what do you mean, no?" She had a good point: Timberland did not have any factories, any customers, or any employees in Darfur, and although she cared about the subject, she didn't come into a shoe store looking to pay for good intentions. Swartz realized that no one understands why buying a Timberland boot, even a cool boot from Don Cheadle, would stop rape and genocide in Darfur or how it's connected to their business mission. Not long after that, a meeting with Bill Clinton crystallized the realization.

"He said, 'Jeff, you think you're a good guy working in the corporate world,'" said Clinton, according to Swartz. "The world thinks that you're a rapacious pillager. The power of selling an idea is not to say, 'No no no.' It's actually to say, 'You're right, you caught me. I want to make a huge amount of earnings for shareholders, and the way I do that is by making the greatest boots in the world and reforesting the world, because if I didn't reforest the world there'd be no place to go hiking and then people wouldn't buy the boots. So it's an evil plot to sell more boots.'" Customers, as it turns out, appreciate the apparent honesty. Since then, Timberland has planted more than one million trees worldwide and pledged to plant five million more in the next five years, a commitment that resonates with its customers and brand.

For a brand firmly rooted in the outdoors, the focus on sustainability is understandable. But from Timberland's perspective, it also makes good business sense. "It saves money and it creates competitive advantage," Betsy Blaisdell sums up. In all the facilities Timberland owns and operates, the company has reduced emissions by 38 percent since 2006, reducing energy costs at the same time. Timberland also contends that when all factors are equal, consumers choose products that are more ecofriendly.

"If we can release a product that is great from a performance standpoint, wonderful from a durability standpoint, and eye-catching from an aesthetic standpoint and provide our consumers with information that demonstrates that it has a smaller environmental footprint than products you might be looking at from other companies, they'll go for the one with the smaller environmental footprint," says Blaisdell. "That's what will push more people toward Timberland products versus those from our competitors."

She might be right. Other companies, from those in Timberland's industry—such as Patagonia, Nike, and Levi Strauss, to name a few—and in other industries, like Pacific Gas and Electric and Texas-based Waste Management, are increasingly integrating commerce with environmental and social responsibility. Meanwhile, business schools across the country have responded with programs that explore the relationship between business and society. Not surprisingly, Tuck has been at the forefront of this evolution with the Allwin Initiative for Corporate Citizenship, which ensures that the changing issues at the intersection of business and society are a key component of the Tuck MBA and the school's broader scholarly activities.

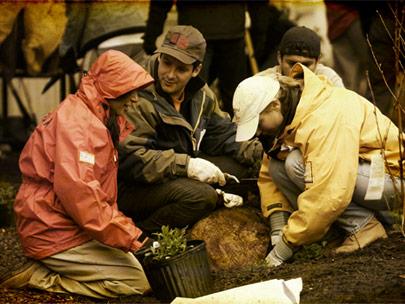

The Allwin Initiative manages the Revers Board Fellows Program, which matches Tuck students with boards of directors at area nonprofits, and facilitates the student-driven Tuck Business & Society Conference, an annual forum for leaders to discuss the role of business in creating a more sustainable world. The initiative's programs also include TuckBuilds, a weeklong preterm program in which students collaborate with local nonprofits on Habitat for Humanity-style projects, and the student-run Tuck GIVES (Grants to Interns and Volunteers for the Environment and Society) auction, also under the Allwin Initiative's purview, which provides an opportunity for members of the Tuck community to support students who accept nonprofit and public-sector internships.

"When I arrived at Tuck in 1994, the students were asking, Should business be involved in society?" says Patricia Palmiotto, director of the Allwin Initiative. "Now the question is how should business be involved in society? I don't think there are any executives today who believe they can go on their merry way and never pay attention to anything outside their operation."

These days, Swartz is most excited about a four-year-old product line called Earthkeepers. The line represents the company's greenest footwear, as rated by the number of harmful chemicals and recycled and organic materials used. By virtue of the manufacturing processes and eco-friendly materials, the line shares a minimalist look. It also showcases innovative new textiles like Bionic canvas, which is made from recycled plastic bottles and organic cotton fibers wrapped around a thin polyester core and happens to be more durable than conventional canvas. But the line isn't just about product. After a slow start, Earthkeepers is now Timberland's fastest growing product line and saw 115 percent growth last year.

"Earthkeepers has the potential to be the place where you tie together, explicitly and sustainably, the notion of commerce and justice," says Swartz. "If we can deliver a sustainable result for the shareholder and a sustainable reality, it'll send the alternatives running for cover." And Jeff Swartz sure wouldn't mind putting the critics out of business.

May 2011