Managing the FBI

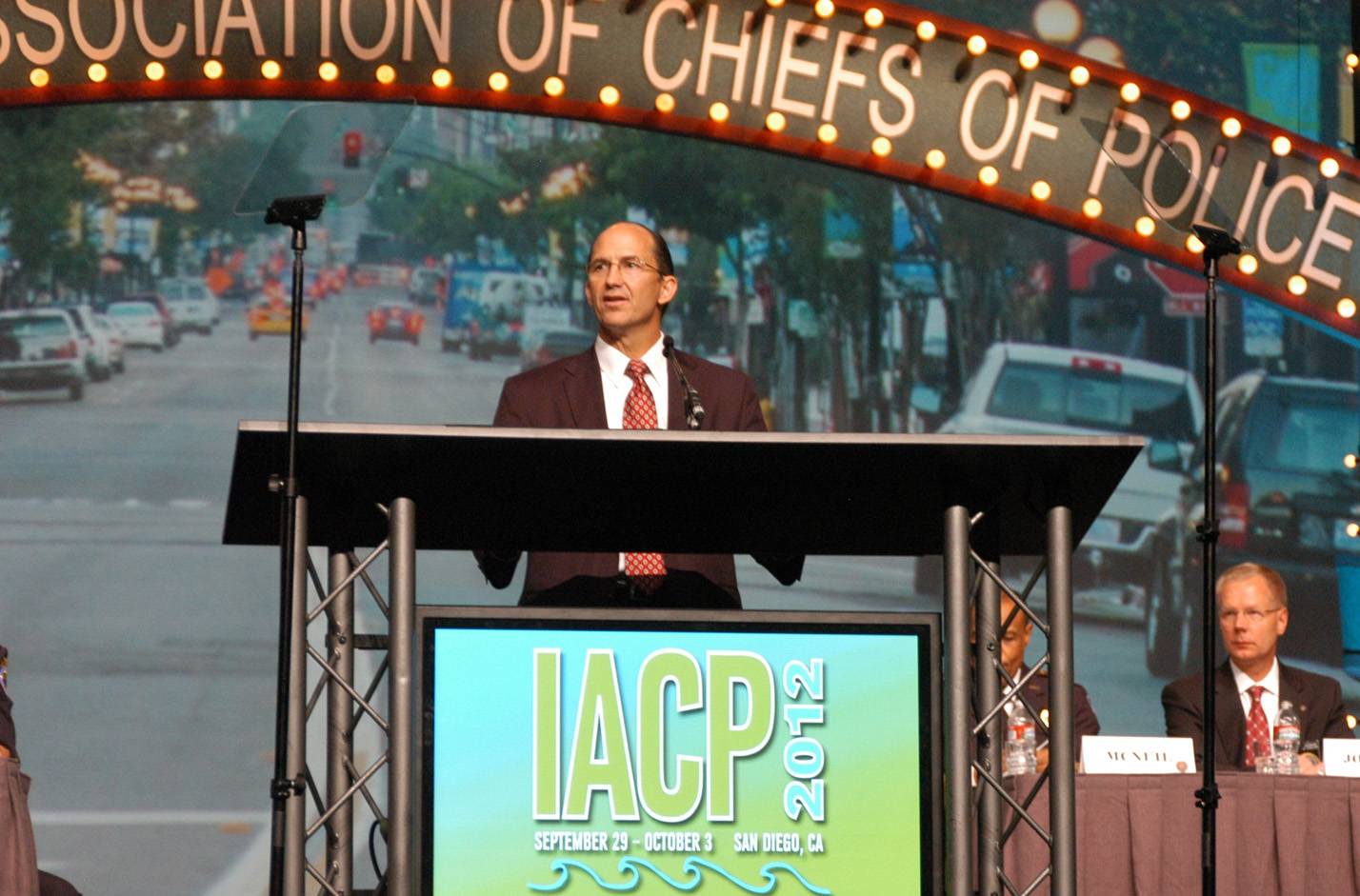

A 25-year veteran of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Sean Joyce T’87 has seen his share of criminals. Now second in command at the agency, Joyce says his business-school education has never been more important.

A 25-year veteran of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Sean Joyce T’87 has seen his share of criminals. Now second in command at the 36,000-employee agency, Joyce says his business-school education has never been more important.

Sean Joyce was in a sailboat floating off the Caribbean island of Bonaire when a plane appeared out of the dusk. Buzzing overhead, the aircraft swooped down and dropped a series of plastic-wrapped bales into the churning open seas. Joyce and several other FBI agents clambered aboard a Zodiac to retrieve the contraband. The bales were stuffed with large quantities of cocaine.

It was 1993 and Joyce was a special agent for the FBI’s Miami Field Office, working on Colombian narcotics cases. For months, he had cultivated sources with connections to the powerful Cali cartel. With their help, Joyce tracked a major cartel figurehead through the streets of Miami. Finally, he and his team arranged for what they called a “test load” by working undercover with cartel representatives in Colombia, and sailed to designated coordinates in the Caribbean Sea for the operation.

After unloading the bales of cocaine onto a Coast Guard boat that night, the team returned to Miami and waited. More than a week later, the cartel, unaware of the trap, divulged the drop-off location at a house in a Cuban neighborhood. Determined not to let the cocaine “walk,” agents hid tracking devices in the bales, outfitted the delivery cars with kill switches, and surveyed the drop-off location with fixed-wing planes. In the evening, agents, including Joyce, swarmed the house and hauled away the drug traffickers, which led to arrests of two of the Cali cartel’s most powerful operatives.

Sean Joyce knows it was at least partly his penchant for adventure that led him on an unusual career path from business school to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, first as a case agent in Texas in 1987 and now in higher management as second-in-command. After one year in his position as deputy director, he is finding that his background in business has never been more critical to success.

Growing up in Brockton, Mass., Joyce focused on having a career in business. So after attending Boston College and working at Raytheon and Arthur Anderson—before it became Accenture—it was no surprise that he landed in business school. Between his years at Tuck, Joyce went to Boston for an internship at Merrill Lynch Capital Markets. There, he specialized in sales and trading, and by the end of recruiting had job offers from both Merrill Lynch and Goldman Sachs. He declined both.

“I guess I took a right turn,” he said. “I enjoyed business but had a different calling.”

Instead, he found a position working as a case agent for the FBI in Texas, investigating cases involving fugitives, bank robberies, kidnappings, and extortions. From there, his resume reads more like a good detective novel than a CEO’s curriculum vitae. In Miami, he tracked down Colombian drug lords as part of the office’s SWAT team, and in Quantico, Va., he served on the FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team, where he helped find Mir Aimal Kasi, who murdered two CIA agents in 1993, in Pakistan. After working as a legal attaché in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the FBI international liaison in the region, he moved to Washington, D.C. There, since 2007, he has climbed the ranks with an unusual rapidity. In just four years, he went from running the FBI’s International Operations Division as assistant director, and then oversaw counterterrorism, counterintelligence, weapons of mass destruction, and intelligence programs as the executive assistant director of the FBI’s National Security Branch. In September 2011, Director Robert Mueller chose him as deputy director of the bureau.

Now Joyce’s duties are largely administrative and most of the doors he opens he doesn’t have to knock down, though his field experience complements a deep knowledge of the inner gears of the FBI. Under the director, Joyce now runs an organization of nearly 36,000 people, with 56 field offices and a budget of $8 billion. In terms of management, the job is surprisingly similar to running a very large business—but with potentially much higher stakes.

In recent years, threats have evolved, especially in the FBI’s counterterrorism efforts, with more homegrown violent extremists, splinter terrorist groups, and uncertain power shifts as a result of the Arab Spring. There are also, of course, threats that come out of nowhere, such as the July shooting at a movie theater in Aurora, Colo., or the August shooting at a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wis.

Meanwhile, the mission of the FBI has evolved to meet the changing threat. A stronger impetus for organization-wide changes came on Sept. 11, 2001. Barely a week had passed after Director Mueller assumed office—on September 4—when the planes crashed into the twin towers, changing everything.

Before 9/11, the bureau was still largely reactive, rather than collecting and analyzing intelligence to thwart potential adversaries. Even some key elements of the agency’s infrastructure were basic. For example, on that terrible day in 2001, there were situations in which the FBI’s antiquated computers were unable to send emails with attachments, so some photographs of the hijackers arrived by FedEx. The FBI needed a drastic overhaul, and the new director, Mueller, was charged with the tremendous task.

In addition to focusing on upgrading the FBI’s computer systems, Director Mueller called for a reengineering of FBI structure and operations to closely focus the bureau on the prevention of terrorist attacks, countering foreign intelligence operations against the U.S., and addressing cybercrime-based attacks and other high-tech crimes—all the while ensuring that the bureau remained dedicated to preserving civil rights.

Much of Joyce’s job involves overseeing the massive changes the FBI is still implementing to become an intelligence-driven organization. One not-so-simple goal is to establish the sprawling agency as the leader in cyber operations, something exemplified by Next Gen Cyber, an initiative focused on combating computer intrusions and network attacks.

It starts with basic training. Under Next Gen Cyber, every special agent will be able to perform basic technological tasks, like unloading the data from a cell phone on-site. On a higher level, the FBI has established Cyber Intrusion Task Forces and Child Exploitation Task Forces in all 56 field offices to spearhead the fight against hacking and Internet-related child prostitution and pornography. There is also the National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force, which is how the FBI coordinates efforts among governmental agencies to prevent cyber attacks, such as hacking that could knock down an electrical grid in a major city, detonate a bomb remotely, or deliver malicious code to millions of Internet users.

Other initiatives more manifestly require business savvy. The FBI not only created a Directorate of Intelligence but streamlined the communication and coordination of intelligence across the bureau and its divisions. With a strategic execution team, the bureau standardized the structure of all field offices and established dedicated teams for intelligence collection and reporting.

“The management end of running a business—dealing with people in particular and thinking through business processes and methodology—really help build robust processes in government,” says Mark Giuliano, Executive Assistant Director of the National Security Branch of the FBI. “Even in the FBI, it’s critical that we not just build a personality-driven legacy. It’s important to find a way to analyze how we are performing versus both our mission and how we are spending the taxpayer’s dollar. I know Sean has tried very hard to do that.”

Joyce has also helped the organization widely implement the Balanced Scorecard, a tool typically used by large businesses and organizations to improve communications and evaluate performance against strategic goals. Another initiative, the Leadership Development Program, fosters comprehensive career development at every stage, from running enrichment programs for young special agents to helping retiring executives find suitable jobs outside of government.

“I really think Director Mueller and many of the executives before me have done a phenomenal job, but we’re still changing and hopefully I have played some role in transforming the FBI into what we call a threat-based intelligence-driven organization,” says Joyce. “That’s where I think a lot of my Tuck background has truly been an asset as far as really dealing with people, managing change in an organization, actually implementing and executing change, and effectively communicating that change.”

Joyce himself is quick to downplay his own accomplishments over the last few years and defer credit to the director and his team. He is the first to admit that he has made every mistake in the book—and learned from them. But he is also driven, passionate about the mission of the FBI, and, by his own admission, impatient. It is perhaps this impatience and this demand for excellence that helps Joyce motivate his team to make the barrage of institutional changes the FBI is still implementing.

“He’s very driven, focused on problem-solving, and a very practical person,” says Gordon Dyal T’87, chairman of investment banking at Goldman Sachs and a friend of Joyce’s. “With his skill set, he obviously could have done a lot of things. I’m not surprised that he’s been successful in the FBI, both as an individual agent as well as in management.”

Today, the positions of director and deputy director at the bureau are jobs in which success is measured, largely, by one overarching metric: whether or not we are attacked again in the same way we were attacked on Sept. 11. It’s difficult to imagine how to live with the weight of such a burden, and perhaps unsurprising that Sean Joyce practically lives at work. But he has faith in his team and faith in the systems and structures that he has helped build.

Still, he goes to bed every night knowing that the first thing he will do in the morning, when he arrives at the monolithic J. Edgar Hoover Building in Washington, D.C., is listen. He’ll listen to a litany of real threats and false alarms—sometimes difficult to distinguish—with the attorney general and top executives from the FBI and CIA. To an outsider, the FBI’s work inevitably appears to be a maze of unanswerable questions, and it’s difficult to imagine living in peace under these conditions. For Sean Joyce, it’s not. In his confident Boston accent, he simply says, “I sleep pretty well at night.”