The Right Stuff

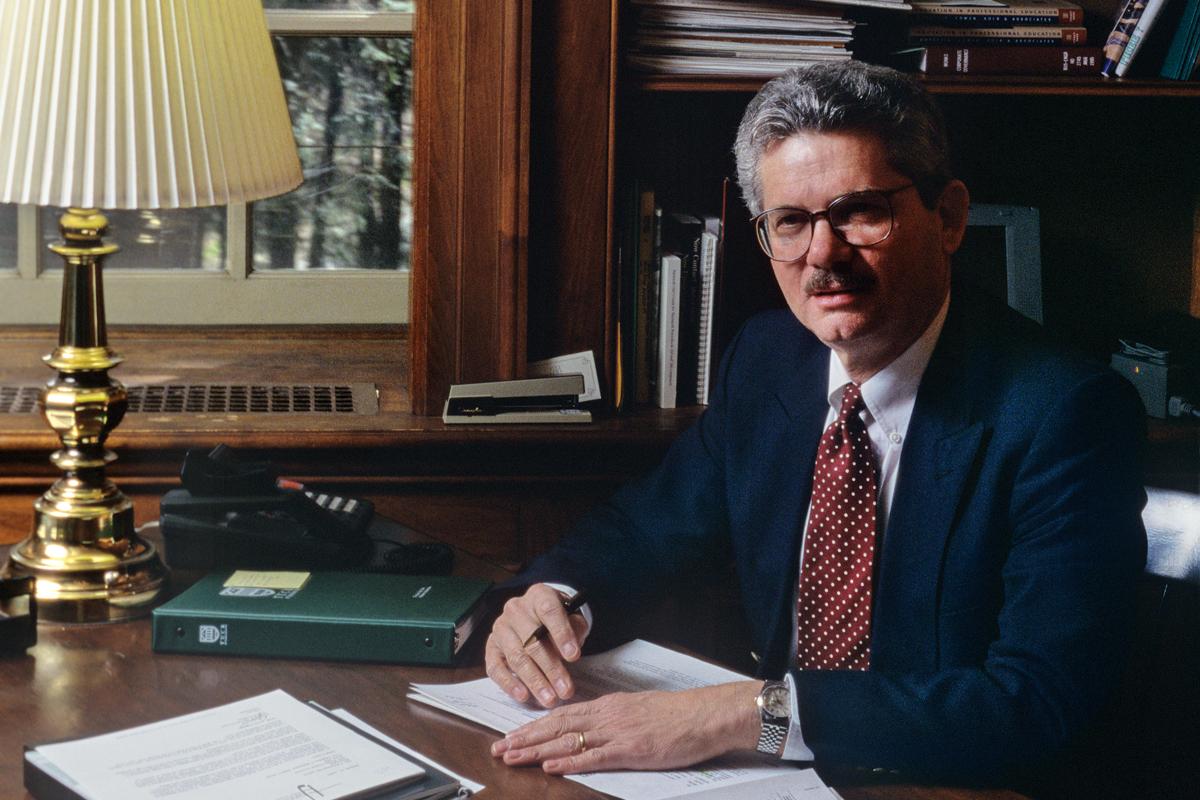

Paul Danos arrived at Tuck armed with big ideas about business education.

Paul Danos arrived at Tuck armed with big ideas about business education and the mandate to make them happen. Twenty years later, the changes he’s made have transformed nearly every aspect of the school and put it on a path for future success. Inside the life and legacy of Tuck’s longest-serving dean.

On a late-winter evening in Chicago, Paul Danos stood before 40 Tuck alumni and talked in a casual way about the smartest decisions he’s ever made. One was marrying his wife, Mary Ellen, more than 50 years ago. They were high school sweethearts and have been together ever since. Another smart decision, he said, was to apply for the job of dean at Tuck, a position he has held since 1995. That makes him the longest-serving dean in Tuck’s history, and puts him near the top of the longevity list for business school deans anywhere. Without a hint of braggadocio, Danos, who wore a green necktie spotted with Tuck shields, noted that most deans of business schools last about four years. “It’s because they don’t know what they’re getting into,” he said. “In my case, I love all aspects of it.”

The alumni had gathered there, in a banquet room on the sixth floor of the University Club of Chicago, to celebrate Danos’ 20 years at Tuck and, in a way, to bid farewell to the man. He is stepping down from the deanship on June 30 and handing the position to Matthew J. Slaughter, Tuck’s current associate dean for faculty and Signal Companies’ Professor of Management. Similar farewell events have taken place in London, New York, Boston, Florida, and other locales. It’s sort of a victory lap for Danos, but he wouldn’t put it that way. He has led the school masterfully through crucial phases of growth and evolution, balancing Tuck’s small-scale residential community with the demands of global recognition, broad faculty expertise, and sophisticated student experiences. Business school rankings are an imperfect measure of these and other characteristics, and usually must be qualified by all sorts of additional information, but they can also be instructive. Before Danos became dean, Tuck’s highest ranking was third. Since 1995, the school has been ranked first eight times.

Celebrating this record in Chicago is fitting, in part because it’s where Danos interviewed for the job in the fall of 1994. Even then, Danos was well respected in higher education. Two years before, Bob Hansen had invited Danos, then a senior associate dean at Michigan’s Ross School of Business, to Tuck to be part of a conference on business school curricula. “That was the first time I met him,” recalled Hansen, a senior associate dean and the Norman W. Martin 1925 Professor of Business Administration at Tuck. “In that audience, you could tell: here was a guy who stood out on the basis of his ideas and his ability to get things done. You could tell he just had a kind of confidence about him as well.” That impression stayed with Hansen, and Danos was on his mind when Tuck began a search to replace Colin Blaydon, who was serving as interim dean after the departure of Ed Fox.

He left and they said, Wow, that’s a guy with really powerful ideas who’s going to be able to make some change." Bob Hansen, senior associate dean and Norman W. Martin 1925 Professor of Business Administration

The interview took place in a hotel by O’Hare airport, a spot chosen more for convenience than atmosphere. “I had great hopes for Paul,” Hansen said. “And I remember thinking during the interview that it was not going well.” Hansen thought Danos was too low-key, that the confident and impressive guy he met two years prior hadn’t shown up. Danos talked to the committee about technology, international reach, research, and the importance of the teaching and learning environment, and Hansen was already convinced that he would be great for the job. But he was worried that Danos wasn’t convincing the rest of the people in the room—a few overseers and faculty members. Hansen needn’t have worried. “He left and they said, Wow, that’s a guy with really powerful ideas who’s going to be able to make some change,” Hansen said.

Paul Danos, who will be 73 in July, was born and raised in Harvey, La., a suburb of New Orleans on the west side of the Mississippi River. His family moved there in the 1930s from Bayou LaFourche, a community of fishermen and one of the first settlements of Acadians who came south from eastern Canada’s Maritime Provinces. Danos’ parents and relatives migrated closer to New Orleans in search of work, and they found it in the booming oil patch of the Gulf of Mexico. Danos’ father started a business servicing oil rigs with barges and tug boats. As soon as Danos was old enough to help out in the company, he was put to work after school and during the summer. By the age of 15, he was the bookkeeper for the family business, learning the job from his older brother.

That was office work, but when school wasn’t in session Danos, a shy kid, was also a deckhand and cook on the vessels his father owned and operated. They usually had a small crew—two or three people—and sometimes towed barges for weeks at a time, traveling across the Gulf from New Orleans to Florida and back. Danos much preferred the books to the boats. “It was days and days of slow movement,” he said. “As a teenager, you want to be out with your friends, be with your girlfriend on the weekends, not somewhere in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico or some godforsaken swamp.” Danos writes about one of these voyages in his short story “The Last Trip,” which appears in a collection of stories he self-published a few years ago called “The Other Side of the River.” In the story, he was co-piloting a barge on the way back to New Orleans from the Port of St. Joe, in Florida, and they float past mansions, pleasure boaters, and water skiers on the Intracoastal Canal. Danos describes the scene:

“I had met this class of people at college, and I was more than ready to have some of their speedboats, summer houses, and all the rest, but most of all I envied the way their parents controlled events. That, to me, was the key; something my father didn’t understand. Just as in the old days when he and his people accepted nature as a force beyond their control, they now accepted commerce as a kind of mystery that ruled them, where unknown people pulled the strings…Now, I believed that if you didn’t want to be swept along helplessly, you had to get a position of control; prayers wouldn’t help.”

The desire to control one’s destiny set Danos apart from his father, and perhaps his father’s entire generation, and it caused him to seek a higher education. Reflecting on that time in his life, Danos said, “I set my sights on being someone who got the knowledge and skills to understand and manage the companies that wield the power in the economy… I work under the assumption that if you dig deep enough and work hard enough you can to some extent control outcomes.” Danos does indeed work hard, and he seems to have been that way since his first days with the family business. As a teenager, it was never questioned that he would be the company’s de facto accountant. After college at the University of New Orleans, he worked full time in the accounting department of Freeport Minerals Company and went to business school at night. On Saturdays, he’d meet up with a few classmates and study. “He never played,” said his wife, Mary Ellen. To this day, Danos doesn’t have any hobbies beyond writing fiction, drawing cartoons, and cooking on the grill. He sleeps four or five hours per night. The rest of the time, he’s working or thinking about work.

Danos had a feeling he would enjoy the academic life, but he wanted to test it out before committing. So he quite his job, applied to the Ph.D. program at the University of Texas at Austin, and when he was accepted he taught accounting for a year at the University of New Orleans. After that experience, he knew he had made the right decision. Soon after, he and Mary Ellen moved to Austin, where he earned his doctorate in accounting in 1974. From there, Danos went directly to the University of Michigan as an assistant professor in the accounting department.

Moving to Michigan was arguably a bigger step than going to Austin. They were leaving the south and would be far from their families; it was a totally different milieu, climate, and culture. The couple doesn’t take such decisions lightly, and Mary Ellen credits some of her husband’s success to that care. “We’re not people that flit,” she said recently while having lunch with Paul in his office. While Paul mostly speaks with an American accent that shows no allegiance to a particular region, Mary Ellen’s voice periodically betrays a southern breathiness and a working-class humility. He probably doesn’t need it, but Mary Ellen is a reminder of his authentic self.

At Michigan, Danos taught a course load that reflected the era, a time before professors stayed in a narrow band of expertise: undergraduate and graduate financial accounting, advanced accounting, managerial accounting, auditing. He wrote textbooks on financial accounting and did research on the auditing industry. He spent 10 years at those pursuits before taking on any administrative work with the school, and another five years juggling teaching and administration.

In 1991, Danos was a full professor of accounting and had been appointed associate dean. That dual role began his intense interest in the optimal business school curriculum, and formed the basis for his goal of enriching the MBA learning experience. Toward that end, Danos joined fellow faculty member Noel Tichy, an action-learning specialist, on a global leadership program expedition to Russia with a group of vice presidents from U.S. and multinational companies. During that trip, Danos and Tichy developed a shared belief that MBA education needed a major infusion of excitement.

Tuck in the early 1990s was going through a minor crisis. The incumbent dean, Ed Fox, resigned in 1994 after one term. In hindsight, according to Bob Hansen, it was probably the right call. “I think there was a little bit of malaise setting into the school at that point,” he said. “We didn’t really have a clear strategy. Faculty weren’t happy, students weren’t happy, so it was a tough time, actually. We needed a direction, and people were looking for someone to rally around.”

Emeritus professor Richard Bower taught managerial economics at Tuck from 1962 to 1999, even though he officially retired in 1990. At 85 years old, he’s still a fixture at the school today, attending talks, faculty seminars, and alumni events. He has short white hair and soft blue eyes, and still portrays remarkable intelligence and strength of mind. Earlier this year, sitting in the office in Woodbury Hall being vacated by Matthew J. Slaughter, he recalled in a quiet but firm voice the general attitude of the faculty when Fox left. “One of the things many of us felt for a long time was that we were missing a really distinguished faculty, academically speaking,” he said. “We had fine teachers who did a wonderful job with the students, but they weren’t across-the-board leaders in their fields.” The only person who wielded enough power to attract such faculty, Bower said, was the dean.

Scott Neslin, the Albert Wesley Frey Professor of Marketing at Tuck, was the associate dean of faculty when Danos arrived, and became Danos’ first lieutenant in the effort to increase the size and expertise of the faculty. “He very much stressed the increasing need for the faculty to be cutting edge,” Neslin said one morning this winter, as light snow fell outside his office window. “The Internet, advances in information processing, and several other factors were accelerating change in the practice of management. This meant the school needed to be on top of the latest research; faculty couldn’t rely on their notes from five years ago.”

Danos, Neslin remarked, understood better than anyone, even the faculty themselves, the lineage of ideas and education: original research begets expertise, and expertise begets effective teaching. In the context of a business school like Tuck, research is valued for its ability to facilitate an intimate learning environment where students interact closely with teachers. Neslin himself is a case in point. “I’ve got a student coming in at 11:30, and we’re going to have an intimate learning experience,” he noted with a smile. They were going to talk about Facebook advertising, something Neslin is currently researching.

For Neslin, working with Danos in the early days of his tenure was exhilarating and fast-paced. “He was a constant flow of energy, creativity, and ideas,” Neslin said. “He was totally immersed in building the faculty, and it was hard work.” The effort was challenging but rewarding. However, Neslin wanted to make sure he had the time to stay at the cutting edge through his research, so he stepped down and Bob Hansen took on the role in 1998. Hansen and Danos worked well together, perhaps because Hansen’s preference for brevity—inspired, he said, by his Finnish heritage—complimented Danos’ natural introversion. “We didn’t have to talk that much,” Hansen said. “We’ve always understood each other and been on the same wavelength.” The numbers bear that out. Today, Tuck has 55 full-time faculty members; 21 more than it had in 1995.

Danos pushed hard on other improvements at Tuck as well. He believed the school was behind its peers in the level of technology on campus, so one of the first major gifts he helped secure was from Fred Whittemore D’53, T’54 for the networked learning labs on the third floor of the Murdough Center. Sensing the imminence of mobile computing, Danos required all incoming students to have laptop computers—a first among business schools. He made Penny Paquette T’76 an assistant dean for strategic initiatives and put her in charge of, among many other things, growing Tuck’s physical footprint from 215,000 square feet 1995 to 360,000 today.

In 1999, partly in response to a recommendation from McKinsey, Danos hired a chief operating officer to oversee much of the administration of the school’s different non-academic departments. He chose an old friend and colleague from his Michigan days, James Danko, for the job. Danko, who is now the president of Butler University, helped usher a range of changes at Tuck, such as the creation of the MBA Program Office, the shift from three sections of 180 students to four sections of 240 students, and the expansion of Executive Education.

Danko was struck by Danos’ strategic thinking about finances. “He wouldn’t be fretting over nickels and dimes,” he said. “He was visionary enough to say, ‘Listen, we’re going to run in the red for a couple of years here, but we’re eventually going to bring in more revenue.’ He had a very broad financial view, but also understood the details.” That strategic use of finance and accounting, Danko said, made possible some of Danos’ most important goals, such as hiring outstanding faculty members. Danos owes this skill to his introduction, at a young age, to balance sheets and ledger books and adding machines. “Most people don’t get that,” Danos said. “They understand the concepts but they don’t really have it deep in their psyche like I do. It was a visceral part of what I did as a teenager.”

M. Eric Johnson, now the dean of the Owen School of Business at Vanderbilt, worked closely with Danos when Johnson became the first faculty director of the Glassmeyer/McNamee Center for Digital Strategies. In 1995, the school didn’t have any of the 10 centers and initiatives it has today, and Danos collaborated with faculty members and administrators to build each one, using a formula that Johnson boils down to one word: momentum. “If you look at any element Tuck was working on, Paul would try to capture the essence of it, build data around that, and then as the process drove forward, show with the data that indeed momentum was being achieved,” Johnson said. Danos brought the same accounting acumen to the contentious and important world of business school rankings. Long before the website Poets & Quants began aggregating the numerous rankings into one list, Danos applied that principle to Tuck. “One of the things Paul did so well was to not allow everyone to get so fixated on a single number,” Johnson said, “but instead to think about the portfolio of rankings and measuring the school across that portfolio. That was very much an accounting kind of idea.”

If pressed, Danos will divulge the one business school metric that he believes rises above the rest: job placement and compensation. “When you think about it,” he said, “everybody kind of loves the school they go to, but not everybody gets the best jobs in the world, because somebody else is making that judgment.” His point, as usual, comes back to Tuck, which is regularly among the top five business schools when it comes to the percentage of students with job offers within three months of graduating (98 percent in 2014), and in terms of total compensation (the median is $166,000), and job satisfaction. “I don’t know of a better test of the whole experience,” Danos asserted.

When Danos was at the University of Michigan, he began teaching a class that would have a profound effect on him and many others. It was a required class for Ph.D. students at the business school, and the topic was the philosophy of science. In the class, he introduced his students to the histories of various fields of study, and to the nature of inquiry and evidence. Teaching that course year after year turned Danos into a rare kind of academic: one who was simultaneously immersed in his own specialty but still keenly aware of the broader world of research into which it fit. “It really helped me in relating to faculty outside my field,” he said not long ago. One form of proof came in something he was given upon his exit from Michigan: a collection of letters from colleagues thankful for his counseling on their research and careers.

That collegiality and knowingness would come in handy at Tuck, where he was building a sort of dream-team of professors, because it allowed him to not only recognize talented thinkers and teachers, but also talk with those he hired and coach them about their work. As dean, Danos put some structure around that process by meeting with each faculty member once per year, a practice that would be all but impossible at larger business schools. “A big part of what a dean does is to understand the motivations of the faculty,” Danos said, “what their expertise is, and what’s the best thing for them to be teaching. And I’m just very interested in their research.”

The meetings are usually long. So much so, according to accounting professor Leslie Robinson, that faculty need to make sure they block out a few hours on their calendar even if the session is supposed to be shorter. “They’re long because he loves to talk about not just what you’re doing but what you could be doing,” Robinson said. “We probably spend 80 percent of the time talking about world problems and what kind of project you could work on to answer these massive questions.” Robinson enjoys these annual meetings because they give her a chance to muse about that one blockbuster paper everyone wants to write in their career. “He’s always trying to get you to think about what it could be, and that’s fun,” she said.

Danos’ talent for career advice seems to go beyond faculty counseling to a more general realm of wisdom. Jim Danko calls Danos the most influential person in his life, next to his own father. That’s because Danos has repeatedly guided Danko in the right direction when job opportunities came up. At one point early in his career in higher education, Danko could have become an adjunct professor at Michigan or the director of the MBA program at the University of Washington. Danko was leaning toward the adjunct position, and had even turned down the offer from Washington, when Danos convinced him he made the wrong decision. So Danko called Washington back, hat in hand, and asked if he could still have the job. The school was already in negotiations with another candidate, but agreed to give Danko the job. After that, he began a series of upward moves that have landed him in the president’s office of Butler, even though he doesn’t have a doctoral degree. “I ended up on a leadership development track in an industry that doesn’t have one,” Danko said.

“Paul kind of sneaks up on you,” he continued. “He’s got a quiet but very confident presence about him. At first blush you might say to yourself, I don’t buy that particular piece of advice. But when you do your homework and get more experience, you realize he was right.”

For the past four years or so, Paul and Mary Ellen have visited the island of Maui for a few days in January. Paul will usually be heading east from a meeting somewhere in Asia, and Mary Ellen will fly west to meet him in Hawaii. They like to go for walks on the beach, or sit and relax on the lanai. This year, they had more time, a full week, and halfway through the vacation Paul said something that shocked Mary Ellen: “This is the first time I feel totally relaxed on a trip.”

“It floored me,” Mary Ellen said, “because he always works. Sometimes people call at home, which is fine. Sometimes he’ll be on vacation and have to go back to the room for a conference call. No problem. But I never realized the extent to which the job is with him 24-7, because of the responsibility of being dean.”

Paul is remarkably stoic about that responsibility, the weight of 228 staff and faculty, 560 students, and 9,750 alumni counting on him in all their different ways. He believes that it’s part of the job, and that the job is supposed to be stressful and make you worry and feel on edge. But if he’s feeling anxious, you wouldn’t know it. His wife wouldn’t even know it, because he doesn’t think it’s right to burden his family with his worries. He doesn’t let anyone see him sweat. He doesn’t show panic.

Soon the pressure will be off, and Danos can sense it. “For the first time since I was a child, I feel like the work is pretty much done, and I can end taking responsibility for an entire organization,” he said. “Some people dread that, but I don’t at all. It just feels like a different phase of life. It was good to now; now this is going to be good, too.”